- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Food Plants Introduced in the Chicama Valley During the Viceroyalty of Peru

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Jose Ismael Alva Ch.

By: José Ismael Alva Ch.

Resident Archaeologist of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex

Andean agriculture and civilization

Agriculture in the Andes was the result of knowledge generated from a long process of experimentation that included the observation of the cycles of nature, the domestication of plants, the development of irrigation techniques and the transformation of the environment. In this panorama, the Andean agricultural development and its surpluses made possible the sustenance of the sedentary population and the construction of the first ceremonial centers around 3800 BC.

Pre-Hispanic agriculture in the Chicama Valley

In the Chicama Valley, located on the northern Peruvian coast, the oldest evidence of consumption of domesticated plants is in the Huaca Prieta. 6500 years ago, these coastal communities had access to a variety of maize and chili peppers (Dillehay, 2017). On the other hand, the use of arid plains as agricultural space dates back at least to the Formative period (1800-200 BC). Precisely, recent research indicates that the desert-like Pampa Mocan, located in the northeastern section of the valley, was occupied for agricultural purposes by the Cupisnique society at the time when it was irrigated by streams that were activated by the effects of the El Niño phenomenon (Caramanica, 2019; Caramanica et al., 2020).

Figure 1. Huaca Prieta at the southern end of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex.

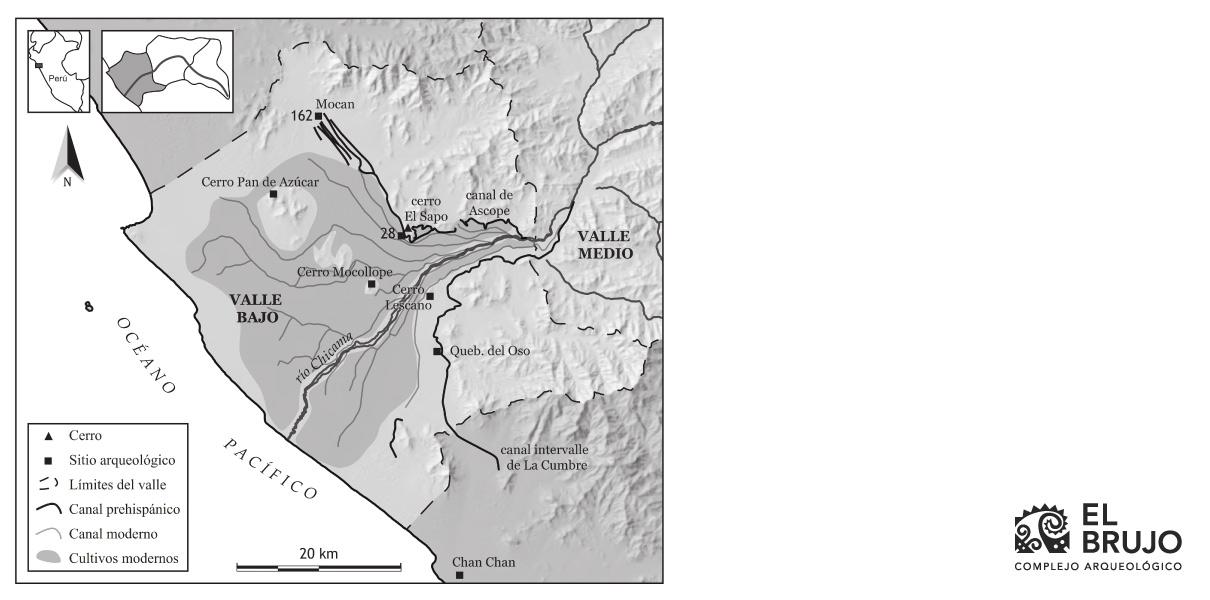

Later irrigation projects, with canals about 15 kilometers long, on the right bank of the Chicama River allowed the Lambayeque to expand agricultural areas (Huckleberry et al., 2017). Further along, the Chimú empire drove the construction of the huge intervalley canal, whose objective was to capture the waters of the Chicama River to direct them to the capital city of Chan Chan. Although its practical purpose has been subject to debate, the intervalley canal represents one of the most notorious state efforts in the region, in terms of material and human resource management (Kus, 1984; Ortloff et al., 1983).

Figure 2. Map of the Chicama Valley with irrigation systems and settlements from the Chimú period. Map published by Camille Clément (Clément, 2016, fig. 2).

Said infrastructure and territorial management made it possible for the peoples settled in the Chicama Valley to have access to cereals (maize), legumes (peanuts, Lima beans, jack beans, common beans and pacae (Inga brachyptera)) and a variety of fruits (soursop, chili, mate, lucuma, avocado, guava, tumbillo or wild passion fruit and friar's plum), just to mention some species, as recorded in the levels associated with the Lambayeque occupation (900-1200 AD) in Huaca Cao Viejo ( Vasquez & Rosales, 1995).

Food plants brought by Europeans

During the first decades of the viceroyalty, many agricultural areas of the Chicama Valley were strongly affected by the demographic decline of its indigenous population and the social reorganization to which it was subject (Alva, 2022). By 1566, Martín Socnamo, one of the curacas (governors) of Chicama, pointed out that the main food plants cultivated by the natives of the valley were maize, chili pepper and beans (Netherly, 1977, p. 79).

In this context, the Spaniards incentivized the cultivation of new botanical species, domesticated outside the Andes. One of the first plants introduced was sugar cane, native to New Guinea (Oceania). Precisely, inside the valley, possibly near Chocope, the first sugar mill in the Chicama Valley was founded in times prior to 1558 (Ramírez, 1995, p. 260). In this place the grinding and processing of the cane was carried out, an activity that turned over the centuries into a profitable economic resource, unfortunately in replacement and to the detriment of a variety of native plants.

Figure 3. Sugar cane today.

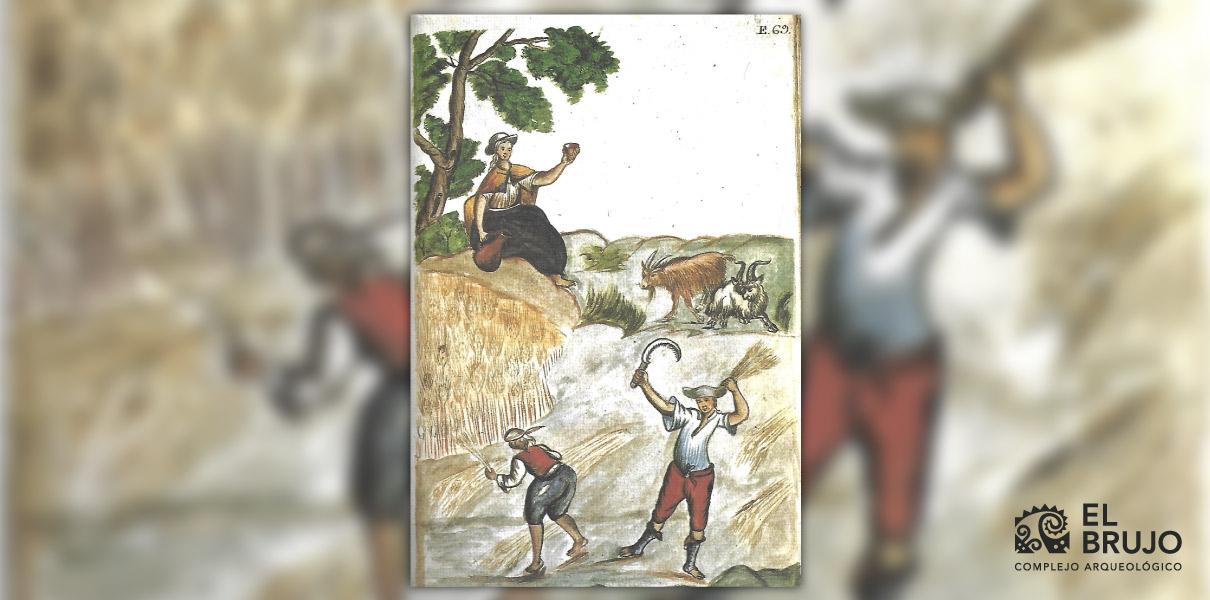

Between 1599 and 1603, the town council of the city of Trujillo decided to prioritize the cultivation of wheat to cover its demand for bread and other derived products. Thus, it appointed a commissioner with the necessary powers to obligate the indigenous farmers of Chicama to plant greater quantities of wheat compared to traditional maize, the cereal that at that time was preferred among the inhabitants of the valley (Larco Herrera, n.d.). In the early nineteenth century, at the dawn of Peru's independence, British explorer William Bennet Stevenson noted that the Chicama Valley came to be known as the breadbasket of Peru, due to the notable production of wheat that it reached during the seventeenth century (Stevenson, 1825, pp. 124-125).

Figure 4. Wheat harvest. Drawing published by Bishop Martínez Compañón (Martínez Compañón, 1985, f. 69).

On December 1, 1740, Spanish expeditionaries Jorge Juan and Antonio Ulloa visited the town of Chocope in the Chicama Valley. In their opus Relación Histórica del Viage hecho por la orden de su magestad a la América Meridional, they underscored the fact that in the vicinity of Chocope "sweet canes, grapes, and many species of fruits are produced luxuriantly, both from Europe and creole ones; and maize in abundance" (Juan & Ulloa, 1748, p. 21). At that time, sugar cane already had a wide distribution from Lambayeque in the north; however, in the Chicama Valley it was "more abundant, and of better quality" (Juan & Ulloa, 1748, p. 22).

Regarding the fruits, the archaeological excavations carried out in the colonial town of Magdalena de Cao of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex have allowed to pinpoint some of the species consumed in the lower valley between the late sixteenth and mid-eighteenth centuries (Quilter, 2020). Thus, the botanical analyses carried out within the framework of Dr. Jeffrey Quilter's research have identified fruits such as peach, orange, lemon, lime and pomegranate (native to Asia), olive, quince and plum (native to the region comprised between Southern Europe and Asia Minor), watermelon (native to Africa), pecan (native to North America) and passion fruit (native to central Brazil).

Final comments

Throughout the pre-Hispanic centuries, the variety of plants of the Chicama Valley has been notable according to archaeological evidence and colonial documents. Although the introduction of new plants in viceregal times increased said diversity, it turned into the progressive replacement of native species. The loss of that richness in food plants is considerable nowadays, given that the monoculture of sugarcane has monopolized the agricultural production of the Chicama Valley, affecting the hills, riparian forests and lagoons.

Knowing these changes in the cultivation of plants allows us to reflect on the present agricultural condition of the valley. This, in order to generate sustainable alternatives that have a positive impact on the quality of life of the inhabitants of Chicama.

Figure 5. Burning of sugar cane in the vicinity of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex. Note Huaca Cao Viejo (left) and Huaca Cortada (right). The burning of sugarcane is one of the most recurrent activities in the valley prior to harvest, this in order to eliminate leaves, weeds and scare away animals. However, it has harmful effects on the environment.

Bibliographic References

Alva, J. (2022). Indigenous territory and society in the valley of Chicama of the sixteenth century. https://www.elbrujo.pe/blog/territorio-y-sociedad-indigena-en-el-valle-de-chicama-del-siglo-xvi

Caramanica, A. (2019). An archaeological study of Pampa de Mocan. In G. Prieto & A. Boswell (Eds.), Proceedings of the First Round Table of Trujillo. New perspectives in the archaeology of the valleys of Virú, Moche and Chicama (pp. 218-230). Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Caramanica, A., Huaman, L., Morales, C., Huckleberry, G., Castillo, L. J., & Quilter, J. (2020). El Niño resilience farming on the north coast of Peru. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(39), 24127-24137. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2006519117

Clément, C. (2016). The Chimú in the Chicama Valley (north coast of Peru): Between the desert and the El Niño phenomenon. In N. Goepfert, S. Vásquez, C. Clément, & A. Christol (Eds.), Andean Societies in the face of Past and Current Changes. Territorial Dynamics, Crisis, Borders and Mobilities (pp. 17-50). Institut français d'études andines / Laboratoire d'Excellence Dynamiques Territoriales et Spatiales.

Dillehay, T. D. (Ed.). (2017). Where the Land Meets the Sea. Fourteen Millennia of Human History at Huaca Prieta, Peru. Texas University Press.

Huckleberry, G., Caramanica, A., & Quilter, J. (2017). Dating the Ascope Canal System: Competition for Water during the Late Intermediate Period in the Chicama Valley, North Coast of Peru. Journal of Field Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2017.1384662

Juan, J., & Ulloa, A. de. (1748). Relación Histórica del Viage hecho por la orden de su magestad a la América Meridional: Vol. Third volume. Antonio Marin.

Kus, J. S. (1984). The Chicama-Moche Canal: Failure or Success? An Alternative Explanation for an Incomplete Canal. American Antiquity, 49(2), 408-415. https://doi.org/10.2307/280029

Larco Herrera, A. (Ed.). (n.d.). Anales de Cabildo, City of Trujillo. Excerpts taken from the proceedings of the years 1598-1604. Sanmarti.

Martínez Compañón, B. J. (1985). Trujillo del Perú: Vol. II (Spanish Agency for International Cooperation).

Netherly, P. (1977). Local Level Lords on the North Coast of Peru [Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology)]. Cornell University.

Ortloff, C. R., Moseley, M. E., & Feldman, R. A. (1983). The Chicama-Moche Intervalley Canal: Social Explanations and Physical Paradigms. American Antiquity, 48(2), 375-389. https://doi.org/10.2307/280459

Quilter, J. (Ed.). (2020). Magdalena de Cao. An Early Colonial Town on the North Coast of Peru (Vol. 87). Peabody Museum Press.

Ramírez, S. E. (1995). Of Fishermen and Farmers: A Local History of the People of the Chicama Valley Before 1565. Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines, 24(2), 245-279.

Stevenson, W. B. (1825). A Historical and Descriptive Narrative of Twenty Years Residence in South America: Vol. II. Hurst, Robinson, and Co.

Vásquez, S., & Rosales, T. (1995). Archaeobotanical study of Zea mayz "maize" and other vegetables associated with excavation No 2, central sector of ceremonial plaza —Huaca Cao Viejo. Andean Archaeological and Paleoecological Research Center "Arqueobios".

Researchers , outstanding news